How To Improve Investment Outcomes In Sustainable Refurbishments

Energy cost savings on their own may not be enough to support a business case, but factor in the potential rental income increase – the more sensitive variable in life cycle analyses – and then sums are more likely to add up. The question is: how and when should you act?

Facilities managers have the potential to contribute to three key objectives facing real estate asset owners and managers; improving an assets’ value, improving an assets’ return and minimizing risks associated with assets obsolescence and increasing energy costs.

A recent study (Hertzsch et.al) illustrates the need for, and benefits of, a holistic approach to the real estate asset management (REAM) decisions making process. The methodology is based on assessing building sustainability upgrades within a life cycle investment strategy.

In practice REAM decisions may be triggered by a variety of events, including equipment breakdown, upcoming lease renewal, end of useful life of a building component, purchase or sale of asset, regulatory requirements, etc. At this point the asset owner or manager faces two decisions; how to act and when to act. The answers to both depend on the expected investment outcomes. Choosing the right investment metric can also be complex. Jaffe and Sirmans (Jaffe and Sirmans, p30) in their paper identified 23 distinct investment objectives, demonstrating the complexity of owners’ objectives and outcomes.

As with any decision making process access to quality data is critical, particularly when investment outcomes are influenced by a diverse set of variables such as construction cost, operational performance, market conditions and revenue projections, cost of capital, taxation treatment, expected sustainability outcomes as measured by NABERS or Green Star rating or sustainability premium, etc. The methodology referred to provides a framework to capture and integrate a variety of data to inform the investment decision process. While the facility manager’s key considerations may be operational – with a focus on a building that works, a building that is efficient and low maintenance – these operational improvements have a direct impact on the building’s asset value but may be sometimes overlooked in the life cycle considerations. In fact, facilities management and asset management are intrinsically linked and, by looking at both, building owners can better optimise the value of their refurbishment projects.

At the recent Green Build Conference, the world’s largest conference dedicated to green buildings, it was reported that 42 per cent of construction work in Australia over the next three years will consist of refurbishment and retrofitting work. The market demand for sustainability upgrades is already significant and growing (World Economic Forum Report).

Owners want to protect their asset value against obsolescence. But equally their hands, to a degree, are being forced. Buildings and equipment naturally come to the end of their service life and are more prone to failure. And regulatory requirements, such as the Commercial Buildings Disclosure Act (2011), are demanding energy efficiency improvements.

Commercial buildings are responsible for approximately 10 per cent of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions and those emissions have grown by 87 per cent between 1990 and 2006.

Energy cost savings on their own may not be enough to support a business case but factor in the potential rental income increase – the more sensitive variable in life cycle analyses– and then sums are more likely to add up. The question then is when should you act? Timing is essential to align improvements and maximize the benefits of any investment.

When this is combined with an oversimplified financial evaluation of outcomes, for example payback periods for specific elements such as variable speed drives, BMS, etc a focus on energy cost reduction and the ignoring of natural life cycle components, then it is little wonder that refurbishment projects don’t always deliver the value they could.

Research collaboration between the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at The University of Melbourne and Meinhardt has looked to provide a more realistic evaluation of refurbishment options and lifecycle investment strategies.

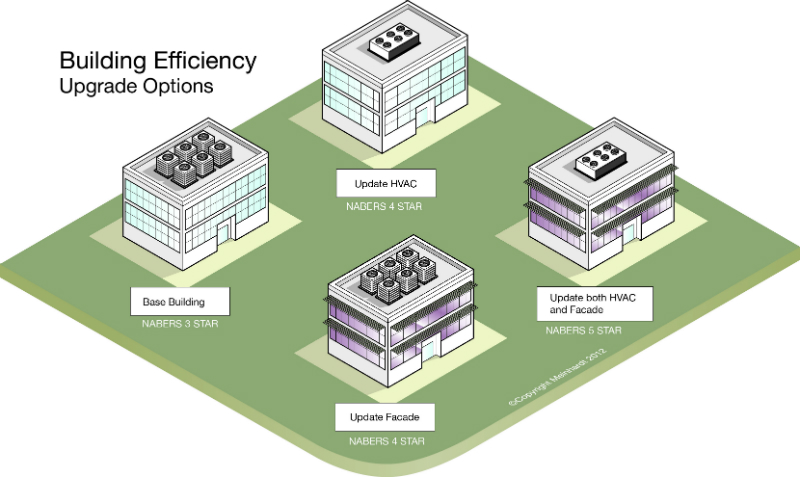

The study took a 21-level office building in Melbourne’s CBD, built more than 20 years, ago as the base model. Detailed energy simulation was then undertaken for seven options, including the base case, a case for heating, ventilation and air-conditioning system (HVAC) upgrade, four cases of façade improvements, and a case combining façade and HVAC upgrade. They were evaluated with regards to their corresponding NABERS rating and financial outcomes.

Both passive design and active design improvements were considered. Passive design initiatives included glazing design, for example improving performance and reducing the glazed area, external shading and natural ventilation. The active design measures included upgrading the HVAC, the Building Management System (BMS) and upgrading lighting controls, such as perimeter lighting.

A lifecycle investment analysis was then carried out. This included measuring the before and after asset investment value of the building.

There were two main trigger points to activate investment. One based on commercial triggers arising when the building’s major lease was up for renewal and the owner and tenant were in the negotiation period; and one based on lifecycle renewal, when the building components reached the end of their useful life. This created a second set of pressure points in relation to the timing of renewing major elements such as HVAC systems.

The research demonstrated that by aligning the timing of a building refurbishment project with the renewal of building components could optimise and improve the investment outcomes. One case considered upgrading 1 year before the chiller – a major component of any building – was due to be at the end of its scheduled lifecycle; the second case, when the project was postponed for a year. Optimised timing of an investment improved the Net Present Value (NPV) outcome by approximately 5%.

This clearly demonstrates the importance of FM’s working collaboratively and communicating closely with AM’s with regards to building component lifecycles.

While the building services component replacement or upgrade can result in tangible operating cost savings, it typically addresses only the P&L aspect of an asset. What the research has shown is that a more comprehensive building upgrade, including the building façade, has the potential to improve both the P&L and Balance Sheet of an asset by moving it up on the building grade scale. This saw a NABERS rating improvement from a low 3 Star to a high 4.5 Star rating. The increase in rental revenue resulting from the building grade improvement can generate enough additional revenue justifying the increased capital expenditure, by making the project NPV positive.

By working together to drive rents up and operations costs down provides clear, tangible justifications for upgrade expenditure.

Dr Mirek Piechowski is Leader – Sustainability, Carbon & Energy (Aus)

References

Hertzsch E, Heywood C, Piechowski M, (2012), ‘A methodology for evaluating energy efficient office refurbishments as life cycle investments’, International Journal of Energy Sector Management, Vol. 6 Iss: 2 pp. 189-212

Jaffe, AJ. And Sirmans, CF. (1986), Fundamentals of Real Estate Investment, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

World Economic Forum, (2011), ‘A profitable and Resource Efficient Future: Catalysing Retrofit Finance and Investing in Commercial Real Estate’, A Multistakeholder Position Report